Insights

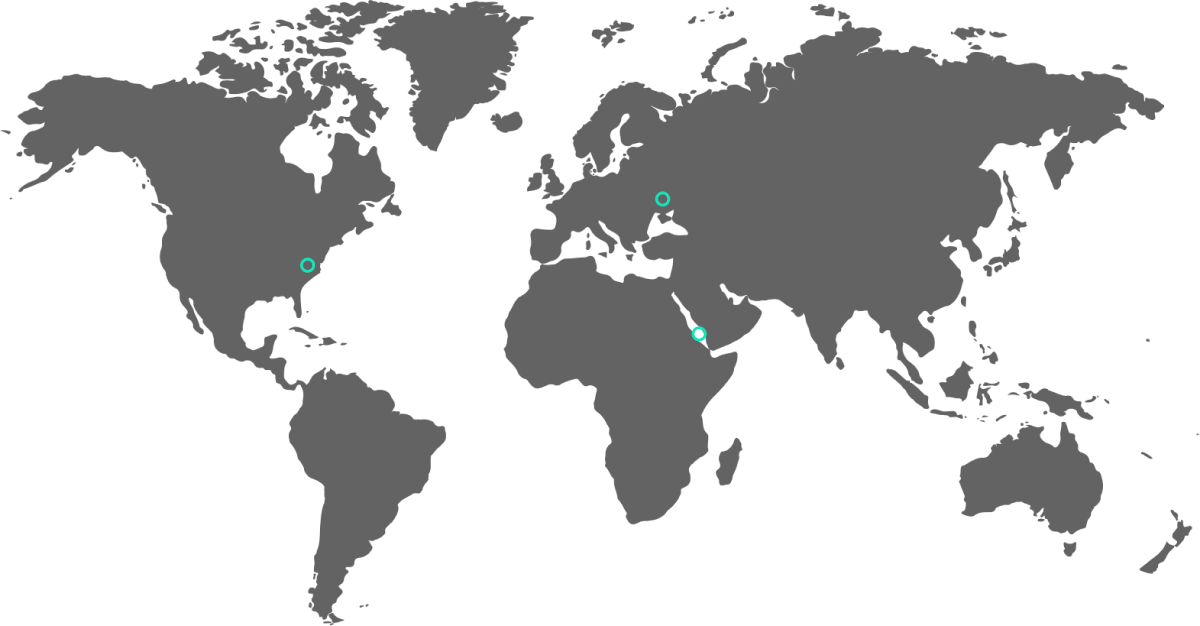

ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA

It took less than an hour for fabricated images of an explosion at the Pentagon to appear on 4Chan, Twitter, Reddit, and other channels on May 22, accumulating 4K mentions before being fact checked by mainstream media.

THE RED SEA

As Houthi-led attacks against vessels transiting the Red Sea have increased, Zignal detected a correlating information operation resulting in an increase of pro-Houthi slogans within the global media environment.

KAKHOVKA, UKRAINE

Within 48 minutes of sunrise on June 6, Zignal’s AI algorithm and critical infrastructure geofence of the Ukraine conflict zone automatically detected damage to the Kakhovka dam.

Leverage Zignal to Understand Key Variables Within the Operational Environment

Political

Global policy, diplomacy, and international elections

Military

Disruptive events, global security, and areas of conflict

Economic

Financial markets, stock manipulation, and supply chain

Social

Beliefs, values, customs, and behaviors within society

Information

Influence operations, technology, and emerging platforms

Infrastructure

Transportation networks, cybersecurity, and facility protection

Physical Environment

Natural disasters, resource supplies, and climate change